MUTAZIONI GENETICHE: UNA HORROR STORY (O QUASI)

- culturainatto

- 31 ott 2021

- Tempo di lettura: 9 min

ITA/ENG

di Aurora Licaj

Translation by the author

Quando viene proposto il termine mutazione, quasi istintivamente ci viene da pensare a qualcosa di negativo, ad una deviazione dalla normalità. In effetti non abbiamo tutti i torti, perché dal punto di vista medico una mutazione è spesso correlata ad una malattia genetica. Al contempo però ha anche un’accezione più positiva, essendo essa il motore dell’evoluzione.

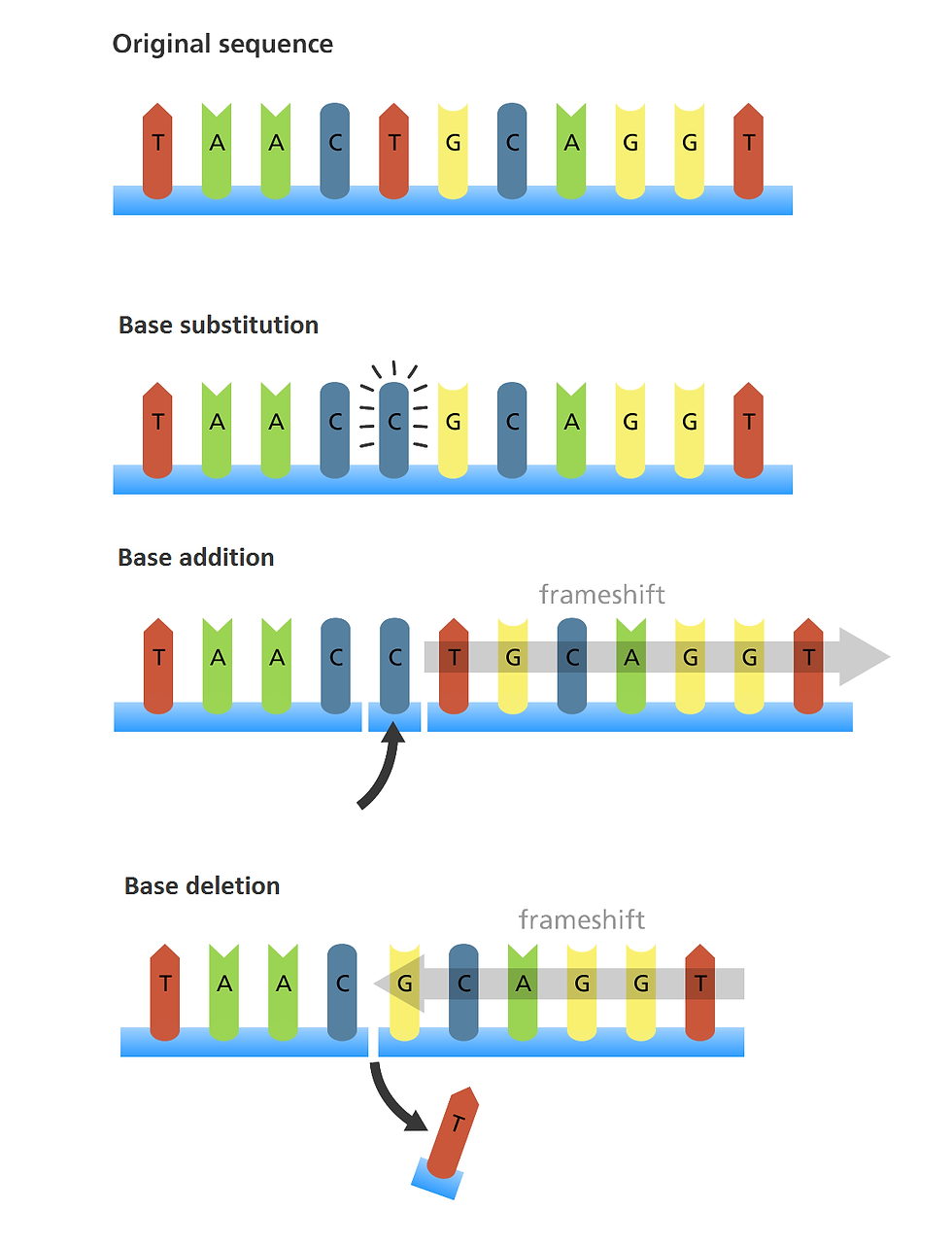

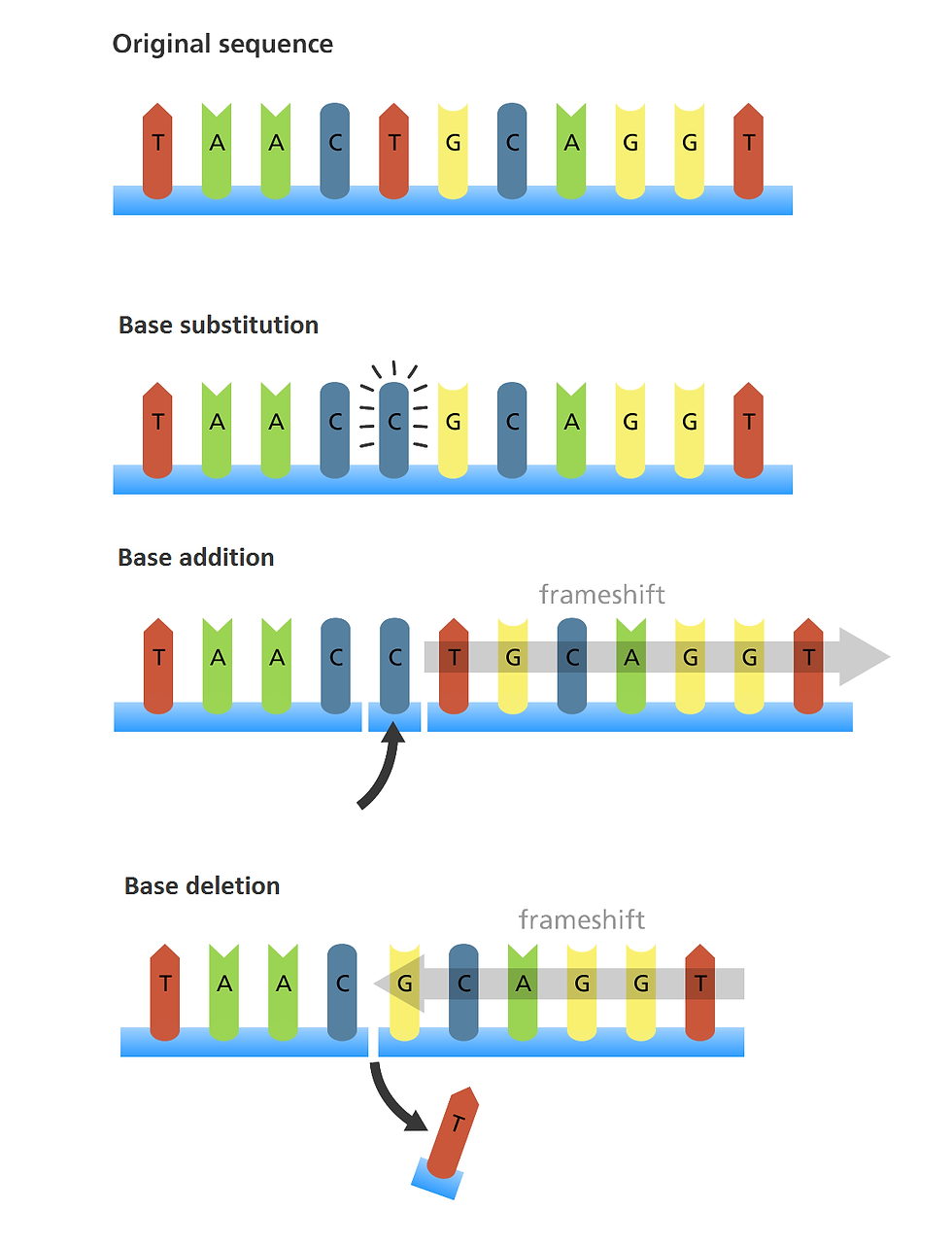

Alla base di tutti questi meccanismi stanno le alterazioni del DNA: infatti le mutazioni sono variazioni della sequenza nucleotidica del DNA [1]. Tra le cause principali ci possono essere errori durante la sua duplicazione oppure danni da esposizione delle cellule ad agenti fisici o chimici (agenti mutageni), ma possono anche essere frutto di eventi del tutto spontanei.

Le alterazioni posso avere svariate dimensioni, si va da interi cromosomi, definite aneuploidie, fino ad arrivare alla più piccola anomalia, le mutazioni puntiformi. Non c'è una correlazione diretta tra le dimensioni della mutazione e la gravità: ci sono mutazioni puntiformi, quindi anche di un solo nucleotide, che sono incompatibili con la vita, dipende sempre dall’importanza del messaggio biologico che contiene il gene colpito. Per esempio, se la mutazione avviene all’interno di una regione di DNA implicata nella produzione di una proteina, possiamo avere un’alterazione della proteina corrispondente e quindi della sua funzione, con conseguenze spesso molto gravi per l’organismo.[2]

Come risultato una mutazione può portare alla perdita di regioni del DNA nel caso delle delezioni, oppure l’integrazione di pezzetti di DNA esterno, le inserzioni. In questo caso vale il motto latino “melius abundare quam deficere”: infatti, di solito, viene tollerato meglio avere qualcosa in più piuttosto che in meno. Può inoltre colpire tutte le cellule tranne che i gameti, definendosi somatica, oppure presentarsi solamente nelle linee germinali. Cosa implica questo? Che una mutazione somatica rimane limitata all’individuo che la porta, mentre una mutazione delle linee germinali può essere trasmessa alla progenie. [3]

Qualunque genetista, quando vi parlerà delle mutazioni, probabilmente affermerà anche che, statisticamente, ciascuno di noi è portatore di almeno due malattie genetiche dovute ad esse, che però non si manifestano (per cui siamo portatori sani [4]); e vedendo la vostra espressione allarmata, vi rassicurerà subito dopo dicendo che è raro che si verifichi l’unione di due individui portatori della stessa mutazione. E proprio mentre stai tirando un sospiro di sollievo continuerà asserendo che, qualora ci fosse un tasso frequente di una malattia genetica in una determinata popolazione, allora non sarebbe più un evento tanto raro. A quel punto penserai che i genetisti siano delle persone sadiche che si divertono a terrorizzarci, ma in realtà la loro intenzione non è quella (forse).

Purtroppo per la nostra specie, come si diceva all’inizio, le mutazioni sono molto frequenti e quindi possono causare malattie più o meno gravi, classificate come letali, subletali o neutre [5]. Ce ne sono alcune che colpiscono grandi fette di popolazione con un quadro clinico da letale a subletale, come in quella caucasica la fibrosi cistica, per cui ogni 25 persone una è portatrice sana; oppure con effetto da subletale a neutro come la beta-talassemia, una malattia dei globuli rossi molto diffusa nelle popolazioni mediterranee [6].

Altre invece sono talmente rare e spesso letali che è difficile poter pensare ad una cura, come nel caso dell’acondroplasia(nanismo) che ha un tasso d’incidenza di 1 individuo su 26.000 o la sindrome di Marfan con 1 individuo su 5.000-10.000 nati vivi.

All’inizio del discorso ho sottolineato come le mutazioni siano però anche fondamentali nel processo evolutivo. Esse per l’appunto contribuiscono alla variabilità genetica, soprattutto in organismi che possiedono un grado di tolleranza ad esse maggiore, come nel caso di piante o altri viventi.

Già Darwin sosteneva che, se una mutazione è vantaggiosa, viene trasmessa nelle generazioni, che in tal modo riescono ad adattarsi meglio alla pressione selettiva esercitata dall’ambiente in cui vivono. Un esempio famoso è quello della Biston Betularia, un tipo di lepidottero che, con l’avvento della rivoluzione industriale nell'Inghilterra del XVIII secolo, iniziò a manifestare con maggior frequenza la variante carbonaria (nera) a causa dell’inquinamento da gas di scarico, fenomeno chiamato melanismo industriale.

Dopo una serie di ricerche si è riusciti a scoprire che questo evento aveva all’origine una mutazione dovuta ad un evento di inserzione di elementi genetici a livello di un gene che dava la variante nera. Questo, insieme alla selezione naturale esercitata dai predatori, che cacciavano la variante bianca che meno si mimetizzava tra i licheni morti per l’inquinamento, hanno contribuito al successo evolutivo della mutazione [7].

Esempi del genere ce ne sono in abbondanza, basti pensare a come le piante sviluppano mutazioni che le rendono più resistenti a certi parassiti o ambienti ostili (che noi riusciamo a selezionare da sempre tramite incroci mirati); e non dimentichiamoci dei nostri amatissimi virus, che grazie ad esse riescono ogni volta a preservarsi rinnovando la loro capacità di contagio [8] …

Insomma, le mutazioni hanno questa doppia personalità con cui dobbiamo fare ogni volta i conti. Da un lato siamo arrivati ad indurle tramite manipolazione genica in laboratorio, per esempio in cellule vegetali nell’intento di migliorare molte specie a fini agricoli, dall’altro si cerca di correggerle nel caso delle malattie grazie alle tecniche più avanzate di terapie geniche e tecniche di gene editing come CRISPR-Cas9 [9]. Sicuramente la loro imprevedibilità può suscitare molto timore nelle menti di ciascuno di noi, ed è per questo motivo che la ricerca al riguardo va incentivata. Perché come diceva Seneca "timendi causa est nescire".

NOTE

[1] Per sequenza nucleotidica si intende la serie di “mattoncini” che costituiscono il DNA, appunto i nucleotidi, che sono adenina (A), guanina (G), citosina (C) e timina (T). A si accoppia sempre con T e G con C. Sono responsabili della struttura ad elica del DNA e contengono l'informazione poi tradotta per la sintesi di proteine nelle cellule. Una sequenza di nucleotidi che da un determinato prodotto genico (proteine o altre molecole) viene definito gene.

[2] Mutazioni in geni che producono proteine possono avere diversi effetti: la proteina non viene prodotta o può perdere la sua funzione, oppure può portare a una sua sovraproduzione o acquisire una nuova funzione diversa da quella iniziale. L’eziologia di molti tumori è proprio legata a queste mutazioni.

[3] Per meglio intenderci, le cellule sessuali come lo spermatozoo o la cellula uovo sono parte della linea germinale.

[4] Un portatore sano è un individuo eterozigote recessivo: per capire meglio il significato vi consiglio di consultare questo link: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/heterozygous

[5] Si definiscono mutazioni letali quelle che causano la morte dell'individuo in fase embrionale o fetale. Subletali quando determinano la comparsa di anomalie compatibili con la vita ma non permettono all'individuo di raggiungere l'età riproduttiva. Neutre quando non causano alcun effetto nell’individuo.

[6] La fibrosi cistica è causata da una delezione di tre nucleotidi che provoca la perdita dell'aminoacido fenilalanina, con conseguente alterazione della corretta escrezione del cloro. Anche la beta-talassemia è conseguenza di una delezione, che altera la struttura dell’emoglobina e provoca globuli rossi molto più piccoli del normale (microciti).

[7] L’articolo originale sullo studio lo trovate su Nature: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature17951 ; per chi non può accedere tramite la propria istituzione, trova una buona spiegazione anche qui: https://wp.unil.ch/genomeeee/2016/12/16/peppered-moth-melanism-mutation-is-a-transposable-element/

[8] Per chi volesse qualche informazione in più sui virus, qui un mio precedente articolo: https://www.culturainatto.com/post/i-virus-qualche-orientamento

[9] Una spiegazione su cosa sia CRISPR-Cas9 la trovate in questo mio articolo: https://www.culturainatto.com/post/che-impatto-ha-nella-nostra-vita-il-premio-nobel-per-la-chimica-2020 . Un articolo sull’editing genetico applicato ad una malattia causata da mutazione: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41434-021-00222-4

GENETIC MUTATIONS: AN (ALMOST) HORROR STORY

When the term mutation is proposed, we almost instinctively think of something negative, a deviation from normality. Actually we’re not all wrong, because from a medical point of view a mutation is often related to a genetic disease. At the same time, however, it also has a more positive meaning, being the fuel of evolution.

At the basis of all these mechanisms are the alterations of the DNA: in fact, the mutations are variations of the nucleotide sequence of the DNA [1]. Among the main causes there may be errors during its duplication or damage from exposure of cells to physical or chemical agents (mutagens), but they may also be the result of completely spontaneous events.

The alterations can have various dimensions, ranging from entire chromosomes, defined aneuploidy, up to the smallest anomaly, the point mutations. There is no direct correlation between the dimensions of mutation and gravity: there are point mutations, therefore even of a single nucleotide, which are incompatible with life, always depends on the importance of the biological message that contains the affected gene. For example, if the mutation takes place within a region of DNA involved in the production of a protein, we can have an alteration of the corresponding protein and therefore of its function, with often very serious consequences for the organism. [2]

As a result, a mutation can lead to the loss of DNA regions in the case of deletions, or the integration of pieces of external DNA, insertions. In this case the Latin motto "melius abundare quam deficere" applies: usually it is better tolerated indeed by the organism to have something more than less. It can also affect all cells except gametes, defining itself as somatic, or present only in the germ lines. What does that imply? That a somatic mutation remains limited to the individual who carries it, while a mutation of the germ lines can be transmitted to the offspring. [3]

Any geneticist, when he will talk to you about mutations, will probably also tell you that, statistically, each of us is the carrier of at least two genetic diseases because of them, which, however, do not manifest (for which we are asymptomatic carriers [4]); and seeing your alarmed expression, he will reassure you immediately afterwards by saying that it is rare for the union of two individuals carrying the same mutation to occur. And just as you’re breathing a sigh of relief, he’s going to go on and say that if there was a frequent rate of genetic disease in a given population, then it wouldn’t be such a rare occurrence anymore. Then you’d think geneticists are sadistic people who enjoy terrorizing us, but that’s not really their intention (maybe).

Unfortunately for our species, as it was said at the beginning, the mutations are very frequent and therefore can cause more or less serious diseases, classified as lethal, sublethal or neutral [5]. There are some that affect large slices of population with a lethal or sublethal clinical picture, as in the Caucasian cystic fibrosis, so every 25 people 1 is a healthy carrier; or with effect from sublethal to neutral as beta-thalassemia, a red blood cell disease widespread in Mediterranean populations [6].

Others are so rare and often lethal that it is difficult to think of a cure, as in the case of achondroplasia (dwarfism) which has an incidence rate of 1 in 26,000 or Marfan syndrome with 1 individual in 5,000-10,000 live births.

At the beginning of the speech, I emphasized how mutations are also fundamental in the evolutionary process. They contribute to genetic variability, especially in organisms with a greater degree of tolerance to them, as in the case of plants or other living beings.

Darwin argued that, if a mutation is beneficial, it is transmitted in the generations, which in this way can better adapt to the selective pressure exerted by the environment in which they live. A famous example is the one about Biston Betularia, a type of lepidopteran that, with the advent of the industrial revolution in England in the eighteenth century, began to manifest more frequently the variant carbonaria (black) because of the pollution from waste gases, phenomenon called industrial melanism.

After a series of research it was found that this event had at the origin a mutation due to an event of insertion of genetic elements at the level of a gene that gave the black variant. This, together with the natural selection exerted by the predators, which hunted the white variant that less camouflaged among the lichens died from the pollution, have contributed to the evolutionary success of the mutation. [7]

There are plenty of such examples, just think about how plants develop mutations that make them more resistant to certain parasites or hostile environments (that we can always select through targeted crossings); and let’s not forget our beloved viruses, that thanks to them can succeed each time to preserve themselves by renewing their ability to contagion…

In short, mutations have this double personality that we have to deal with every time. On the one hand, we have managed to induce them by gene manipulation in the laboratory, for example in plant cells with the aim of improving many species for agricultural purposes, on the other hand, attempts are being made to correct diseases through the most advanced gene therapy and gene editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 [8]. Surely their unpredictability can arouse great fear in the minds of each of us, and that is why research in this regard must be encouraged. Because as Seneca said, "timendi causa est nescire".

NOTES

[1] Nucleotide sequence means the series of "bricks" of which the DNA is composed, precisely the nucleotides, which are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T). A always pairs with T and G with C. They are responsible for the DNA helix structure and contain the information then translated for protein synthesis in cells. A sequence of nucleotides that gives a certain gene product (proteins or other molecules) is called gene.

[2] Mutations in genes that produce proteins can have several effects: the protein is not produced or may lose its function or may lead to its over-production or acquire a new function other than the initial one. The aetiology of many cancers is precisely linked to these mutations.

[3] Sexual cells such as sperm or egg cells are part of the germ line.

[4] A healthy carrier is a recessive heterozygous individual: to better understand the meaning I suggest you consult this link: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/heterozygous

[5] Lethal mutations are those that cause the death of the embryonic or foetal individual. Sublethal when they determine the appearance of life-compatible abnormalities but do not allow the individual to reach reproductive age. Neutral when they do not cause any effect in the individual.

[6] Cystic fibrosis is caused by a deletion of three nucleotides that causes the loss of the amino acid phenylalanine, resulting in alteration of the correct excretion of chlorine. Beta-thalassemia is also a consequence of a deletion, which alters the structure of haemoglobin and causes much smaller red blood cells than normal (microcytes).

[7] The original article on the study can be found in Nature: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature17951 for those who cannot access through their own institution, also finds a good explanation here: https://wp.unil.ch/genomeeee/2016/12/16/peppered-moth-melanism-mutation-is-a-transposable-element/

[8] An explanation of what CRISPR-Cas9 is can be found in this article of mine: https://en.culturainatto.com/post/che-impatto-ha-nella-nostra-vita-il-premio-nobel-per-la-chimica-2020-1 . An article on genetic editing applied to a disease caused by mutation: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41434-021-00222-4